This is a book about skimmers. But don’t let that turn you off, because these were a damn’ fine bunch of skimmers.

This is a book about skimmers. But don’t let that turn you off, because these were a damn’ fine bunch of skimmers.

Early on the morning of 25 Oct 44, off the east coast of Samar, in the Philippines, TU 77.4.3 – a small force consisting of six escort carriers, three destroyers and four destroyer escorts, commanded by Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague – found itself face to face with a Japanese force consisting of four battleships (including Yamato, the largest battleship ever built), six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and eleven destroyers, commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita.

A few hours earlier, the Americans had been monitoring the TBS circuit as Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf’s battle force met another Japanese fleet, sinking two battleships, a heavy cruiser and three destroyers. (Only one destroyer escaped.) When Sprague’s crews first sighted their opponents, they thought they were seeing the survivors of the earlier battle fleeing to the north. They were soon disabused of this notion, when Yamato opened fire at a range of twenty miles.

Kurita had lost three cruisers to submarines on the 23rd (two sunk, one damaged and forced to turn back, with two escorting destroyers). The battleship Musashi had been sunk and another heavy cruiser crippled (turned back, along with another destroyer) by aerial attacks on the 24th. Now, fooled by rain squalls sweeping through the area – and also, perhaps, by wishful thinking – he thought he had found Halsey’s fleet carriers, with an escorting force of cruisers. He closed to attack.

Kurita had lost three cruisers to submarines on the 23rd (two sunk, one damaged and forced to turn back, with two escorting destroyers). The battleship Musashi had been sunk and another heavy cruiser crippled (turned back, along with another destroyer) by aerial attacks on the 24th. Now, fooled by rain squalls sweeping through the area – and also, perhaps, by wishful thinking – he thought he had found Halsey’s fleet carriers, with an escorting force of cruisers. He closed to attack.Sprague did the only thing he could do – got as many aircraft into the air as he could, and then ran. Each carrier’s air wing consisted of around thirty Wildcat fighters and Avenger torpedo bombers. Unfortunately, the planes had been preparing for strikes against Japanese targets on Leyte and Samar, and there was no time to rearm them for their new targets. But they pressed the attack, dropping their bombs and firing their rockets, and then returning for one dummy run after another on the Japanese. The latter, of course, had no way of knowing if the approaching aircraft were really attacking or not, and were forced to spend time and effort evading instead of concentrating on their real targets.

While the carriers were running and the aircraft were doing their best to distract the foe, the destroyers turned to attack. Led by USS Johnston (DD-557), they launched torpedoes and closed to within range of their 5” guns. Destroyers dueling with cruisers and battleships; fortunately for the tin cans, armour-piercing shells meant for use against other capital ships simply punched through their thin hulls, in one side and out the other, not exploding unless they hit something good and solid. The destroyers’ torpedoes were a real blessing, crippling the heavy cruiser Kumano and taking Yamato out of the fight as she ran north for ten whole minutes, away from the American ships, to evade.

While the carriers were running and the aircraft were doing their best to distract the foe, the destroyers turned to attack. Led by USS Johnston (DD-557), they launched torpedoes and closed to within range of their 5” guns. Destroyers dueling with cruisers and battleships; fortunately for the tin cans, armour-piercing shells meant for use against other capital ships simply punched through their thin hulls, in one side and out the other, not exploding unless they hit something good and solid. The destroyers’ torpedoes were a real blessing, crippling the heavy cruiser Kumano and taking Yamato out of the fight as she ran north for ten whole minutes, away from the American ships, to evade.After two and a half hours, Kurita had had enough. He had lost tactical control of his ships, two more heavy cruisers (Chikuma and Chokai) were crippled, several other ships (including battleships Kongo and Haruna) were damaged, and the American aircraft had been joined by planes from neighbouring task units, these properly loaded for attacking ships. By this time he had also been made aware of the fact that he was not really facing Halsey’s fleet carriers. The Japanese turned to flee, leaving behind an American force that should have been easy prey for their guns.

The Americans had lost one carrier (USS Gambier Bay CVE-73, the only American carrier ever sunk by gunfire) and three tin cans (Johnston, USS Hoel DD-533, and USS Samuel B Roberts DE-413*); another carrier (USS St Lo CVE-63) was sunk by a kamikaze a couple hours later. Japanese losses, in addition to those of the preceding two days, were three heavy cruisers (Chikuma, Chokai and Suzuya).

The Americans had lost one carrier (USS Gambier Bay CVE-73, the only American carrier ever sunk by gunfire) and three tin cans (Johnston, USS Hoel DD-533, and USS Samuel B Roberts DE-413*); another carrier (USS St Lo CVE-63) was sunk by a kamikaze a couple hours later. Japanese losses, in addition to those of the preceding two days, were three heavy cruisers (Chikuma, Chokai and Suzuya).It was an incredible day, filled with incredible men. One such was GM3/c Paul Henry Carr, of the Samuel B Roberts:

A Japanese destroyer stood nearby, lobbing the occasional shell into the Samuel B Roberts’s ruined mass. The ship took four more hits while the abandon ship effort was under way. Water was lapping up over the port side of the destroyer escort’s fantail when machinist’s mate second class Chalmer Goheen went to check on Paul Henry Carr’s gang back in Gun 52. The gun had been silent since the muffled thud of the breech explosion. Where the water hadn’t yet reached, the decks were covered with burning oil. Goheen crossed the deck, peered into the gun mount’s ripped hatch, and found a horrific scene. Most of the men inside had been obliterated by the blast. They had gotten off 324 rounds of the 325 the ship carried in its after magazine, firing the last seven or eight shells without a working gas ejection line to clear the breech, until one of the final rounds got them.Carr was awarded the Silver Star (posthumously) for his part in the battle. Sprague and numerous others were awarded the Navy Cross, and Commander Ernest Evans, skipper of the Johnston, received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Looking into the mount, Goheen discovered where the magazine’s last round was. It was right there before him, cradled in the arms of Paul Carr himself. The man was alive – though barely, torn from his neck to his groin. Carr was struggling to hold the shell. He begged Goheen to help him load it into the wrecked breech tray. Goheen took the shell from Carr’s arms and laid the gunner’s mate on the floor of his mount. Then he took seaman first class James Gregory, whose leg had been severed near the hip, and carried him out and set him on deck. When Goheen returned to the mount, Carr was on his feet again, shell cradled weakly in his arms. Goheen took the shell from Carr again, lifted him, and carried him out to the deck.

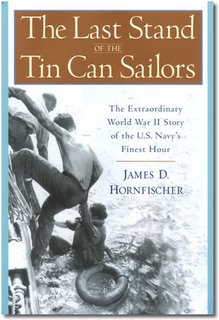

I very highly recommend this book. My only serious complaint is that I would have liked to have seen a little more from Japanese sources. It was published in 2004, and should still be available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other sources.

The photo at the top of this article shows Gambier Bay under attack; a Japanese cruiser can be seen on the horizon, at right. The other ships pictured, from top to bottom, are Hoel, Johnston and Samuel B Roberts. For additional information about the Battle of Samar, see here and here.

* Forty-four years later, on 14 Apr 88, another Samuel B Roberts - FFG-58 – entered history when it hit a mine in the Persian Gulf. Ten men were medevac’d, but none were lost, and the ship was saved.

2 comments:

I think I've just added another book to my pile. Thanks for the review.

Navy Times had two or three pages on No Higher Honor a week or two back. I've added it to my list of books to read.

Post a Comment